- The Launch Dock

- Posts

- THE LAUNCH DOCK

THE LAUNCH DOCK

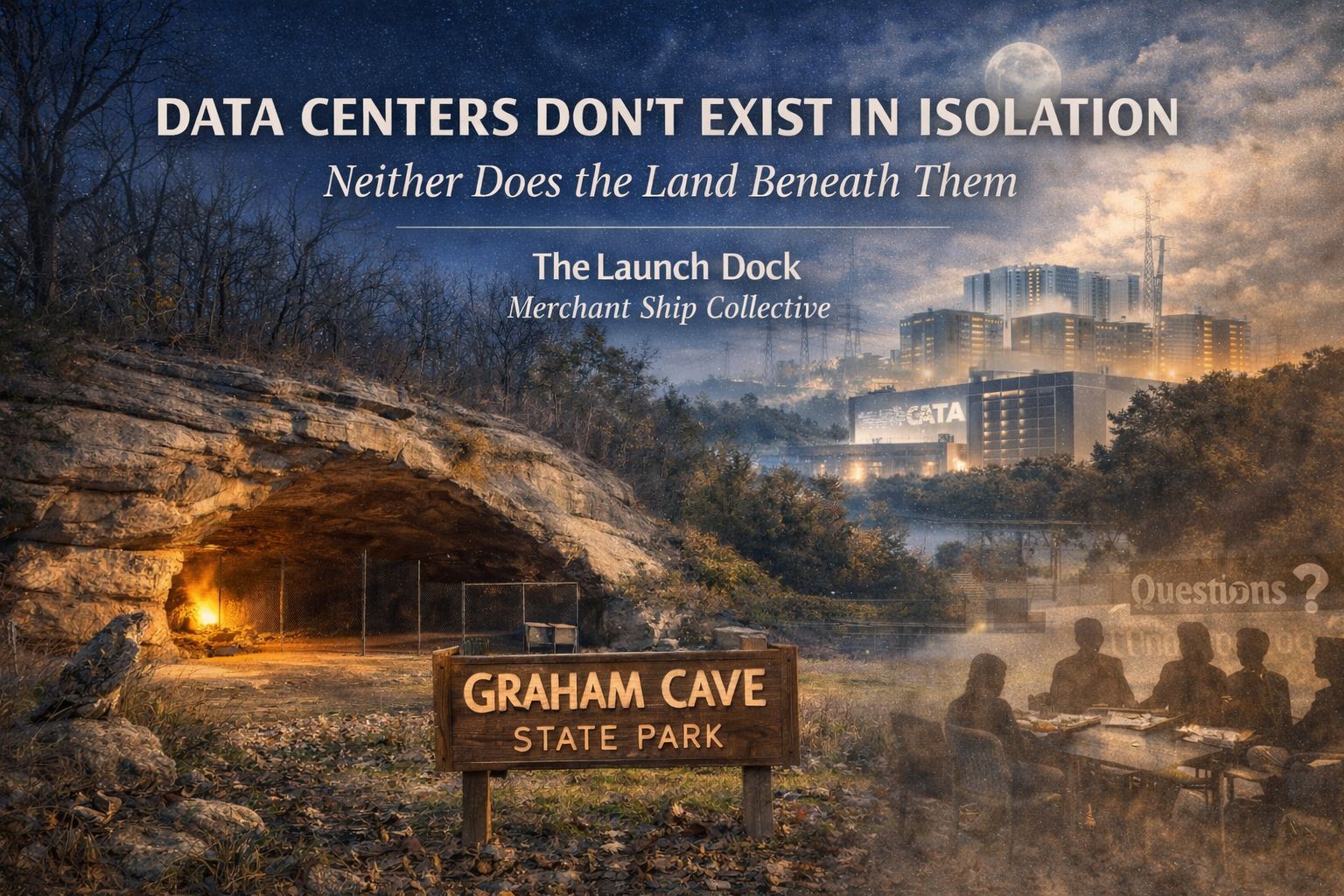

Invisible Infrastructure, Visible Consequences

How Data Centers Reshape Land, Ecology, and Governance Long Before Construction Begins

Some Places Cannot Be Replaced

Not all land is interchangeable.

Some places carry ecological memory.

Some carry cultural meaning.

Some carry responsibility.

When development arrives near protected land, the question is no longer whether growth is legal.

It is whether growth is compatible with stewardship.

And whether decisions were made with full awareness of what stands to be altered—permanently.

When Industrial Scale Meets Protected Land

Proposed large-scale development near New Florence does not exist in isolation. It sits within proximity of land explicitly preserved for conservation, education, and historical integrity, including:

Graham Cave State Park — a site of archaeological significance, ecological preservation, and public heritage

Beth Winter Prairie — a remnant Missouri prairie used for education, conservation, and ecological restoration

Danville Conservation Area — protected land supporting wildlife, watershed health, and public access

These areas were preserved precisely because Missouri has already lost more than 99% of its original prairie ecosystems.

Once disrupted, they do not regenerate on industrial timelines.

Environmental Impact Is Not Just Footprint — It’s Pressure

Large data centers affect surrounding land even when boundaries are respected.

Common secondary impacts include:

Thermal load altering nearby microclimates

Light pollution disrupting nocturnal wildlife and migratory patterns

Noise pollution from continuous cooling systems

Hydrological stress through altered runoff and aquifer drawdown

Habitat fragmentation reducing conservation buffer effectiveness

Expansion pressure through phased growth

None of these require environmental violations to occur.

They emerge from scale.

Conservation as Branding vs. Conservation as Boundary

One of the least discussed dynamics in modern development is reputational adjacency.

When industrial projects sit near conservation land, schools, or public nature trails, they benefit indirectly from the language of sustainability, stewardship, and education—even if their operations are fundamentally extractive.

This is not inherently deceptive.

But it becomes problematic when proximity is used to imply alignment.

A prairie does not offset aquifer drawdown.

A trail sign does not mitigate industrial heat.

A sponsorship does not substitute for ecological limits.

A Hypothetical — But Familiar — Governance Pattern

Consider a hypothetical rural community:

A member of a regional economic development committee helps advance site readiness

That same individual serves on a local school board

Their private business benefits indirectly from growth, contracts, or visibility

The school later receives infrastructure improvements, sponsorships, or partnerships tied to “community investment”

No laws are broken.

No votes are improperly cast.

No disclosures are missing.

And yet:

Influence compounds

Dissent becomes socially costly

Questioning feels disloyal

Outcomes feel inevitable

This is not corruption.

It is structural entanglement.

Why Schools Are Especially Sensitive Spaces

Schools are trusted institutions.

When economic development narratives intersect with education, risks emerge:

Normalizing industrial presence for future generations

Framing development as inevitable rather than debatable

Limiting critical inquiry under the banner of opportunity

Creating implicit pressure on educators and families to “get on board”

Education should expand questions—not narrow them.

Other Concerns Communities Rarely Hear About Early

Beyond land and water, large data center development raises additional long-term questions:

Energy lock-in prioritizing industrial loads over residential needs

Emergency services strain (fire suppression, hazardous materials response)

Decommissioning risk once facilities age out

Insurance and liability exposure decades later

Governance fatigue as complexity suppresses oversight

These are not speculative fears.

They are documented challenges in regions that approved similar projects years ago.

What Responsible Transparency Would Look Like

True transparency would mean:

Acknowledging proximity to protected land as a material factor

Explaining cumulative environmental pressure—not just compliance

Disclosing early coordination timelines

Separating educational institutions from promotional narratives

Inviting scrutiny before momentum makes it awkward

Transparency does not stop development.

It disciplines it.

Methodology

This article draws on conservation management principles, environmental impact frameworks, land-use planning standards, and publicly available economic development practices. No individuals or entities are accused of wrongdoing. Hypothetical examples are used to illustrate structural patterns. Readers are encouraged to review public records and conduct independent research.

Closing: Stewardship Is a Choice, Not a Label

Protected land exists because earlier generations chose restraint.

The question now is whether modern development will honor that inheritance—or quietly surround it until protection becomes symbolic.

Growth without reflection is not progress.

It is acceleration without direction.

And direction is still something communities can influence—if they are allowed to see the full map.

In solidarity,

Lyndsay LaBrier

Merchant Ship Collective

The Launch Dock

References

McLaren, J. D., Buler, J. J., Schreckengost, T., Smolinsky, J. A., Boone, M., van Loon, E. E., Dawson, D. K., & Walters, E. L. (2018). Artificial light at night confounds broad-scale habitat use by migrating birds. Ecology Letters, 21(3), 356–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12902

Shehabi, A., Smith, S. J., Sartor, D. A., Brown, R. E., Herrlin, M., Koomey, J. G., Masanet, E., Horner, N., Azevedo, I. L., & Lintner, W. (2016). United States data center energy usage report (LBNL-1005775). Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. https://eta.lbl.gov/publications/united-states-data-center-energy

Siddik, M. B., Shehabi, A., & Marston, L. (2021). The environmental footprint of data centers in the United States. Environmental Research Letters, 16(6), 064017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abfba1

Missouri Department of Conservation. (n.d.). Graham Cave State Park. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/places/graham-cave-state-park

Missouri Department of Conservation. (n.d.). Danville Conservation Area. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/places/danville-conservation-area

Missouri Department of Conservation. (n.d.). Danville Glades Natural Area. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/places/danville-glades-natural-area

U.S. Department of Energy. (2020). Energy and water use in data centers. https://www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/data-centers